Tuesday, January 23, 2007

Photographer crush - Jen Davis

Deprivation by Jen Davis, via the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago.

Also, a link to Davis's work at the Schneider Gallery in Chicago.

I saw these images in the open portfolio session at the end of S.P.E. in 2006 and they floored me. They are incredibly powerful self-portraits.

From her artist's statement:

When I look at my self-portraits, I see what the outside world must see as I am judged on the basis of the size I am today. This process of self-exploration has helped to lay the foundation of finding my voice, the true identity of who I am, accomplished after peeling away all of the layers created from a lifestyle of a "big girl".

My work is solely based on personal experiences that I have re-constructed into a photograph, but I believe that it speaks generally to the situation of many women in our contemporary culture.

Reuters guidlines for using photoshop.

Found this through the lightstalker's blog this morning:

http://blogs.reuters.com/2007/01/18/the-use-of-photoshop/

A list of things photojournalists submitting to Reuters are and are not allowed to do. From the article:

THE GUIDELINES ARE:

Only minor Photoshop work should be performed in the field.

(Especially from laptops). We require only cropping, sizing and levels with resolution set to 300dpi. Where possible, ask your regional or global picture desks to perform any required further Photo-shopping on their calibrated hi-resolution screens. This typically entails lightening/darkening, sharpening, removal

of dust and basic colour correction.

When working under prime conditions, some further minor Photo-shopping (performed within the above rules) is acceptable.

This includes basic colour correction, subtle lightening/darkening of zones, sharpening, removal of dust and other minor adjustments that fall within the above rules. Reuters recommendations on the technical settings for these adjustments appear below. The level of Photoshop privileges granted to photographers should be at the discretion of the Chief/Senior Photographers within the above guidelines. All photographers should understand the limitations of their laptop screens and their working environments.

Photographers should trust the regional and global pictures desks to carry out the basic functions to prepare their images for the wire. All EiCs and sub editors from regional and the global desks will be trained in the use of Photoshop by qualified Adobe trainers to a standard set by senior pictures staff. The photographer can always make recommendations via the Duty Editor. Ask the desk to lighten the face, darken the left side, lift the shadows etc. Good communication with the desk is essential.

I guess I have always felt that my powerbook was up to the task, and that many of my corrections were based on the numbers in the info palette, so why worry too much about using a laptop monitor. May be time to re-think that. I think I'd have a hard time working like this, I figure that the work in photoshop is where the image really happens.

http://blogs.reuters.com/2007/01/18/the-use-of-photoshop/

A list of things photojournalists submitting to Reuters are and are not allowed to do. From the article:

THE GUIDELINES ARE:

Only minor Photoshop work should be performed in the field.

(Especially from laptops). We require only cropping, sizing and levels with resolution set to 300dpi. Where possible, ask your regional or global picture desks to perform any required further Photo-shopping on their calibrated hi-resolution screens. This typically entails lightening/darkening, sharpening, removal

of dust and basic colour correction.

When working under prime conditions, some further minor Photo-shopping (performed within the above rules) is acceptable.

This includes basic colour correction, subtle lightening/darkening of zones, sharpening, removal of dust and other minor adjustments that fall within the above rules. Reuters recommendations on the technical settings for these adjustments appear below. The level of Photoshop privileges granted to photographers should be at the discretion of the Chief/Senior Photographers within the above guidelines. All photographers should understand the limitations of their laptop screens and their working environments.

Photographers should trust the regional and global pictures desks to carry out the basic functions to prepare their images for the wire. All EiCs and sub editors from regional and the global desks will be trained in the use of Photoshop by qualified Adobe trainers to a standard set by senior pictures staff. The photographer can always make recommendations via the Duty Editor. Ask the desk to lighten the face, darken the left side, lift the shadows etc. Good communication with the desk is essential.

I guess I have always felt that my powerbook was up to the task, and that many of my corrections were based on the numbers in the info palette, so why worry too much about using a laptop monitor. May be time to re-think that. I think I'd have a hard time working like this, I figure that the work in photoshop is where the image really happens.

Monday, January 22, 2007

Creating a digital image library with MDID.

The art historian in my department and I have undergone a push to create an art historical image database using the MDID database system from James Madison University. Researching the system involved a lot of lurking on listservs and web sites, and no one ever seemed to put all of the pieces we needed in one place. So, I am putting a copy of a letter I sent to my dean about the project here on the blog. I hope that someone who is in our position can stumble upon it and have a useful resource.

This summer the department’s art historian and I researched and began assembling a digital slide library. I wanted to apprise you of the scope of our research, the equipment we have put in place, and our plan to move forward for the next year.

Our art historian discussed this move with a number of art historians at other schools and we both searched through the archive of the Visual Resource Association web site (http://www.vraweb.org). One thing is clear; this is no simple undertaking. Most institutions have full time visual resource librarians with a staff helping them. They are often overwhelmed by the complexity of the job, and find the process time-consuming.

The other thing that became clear is that the real issue for slide librarians isn’t software or slide scanners (although they are important). The real issue is metadata. Metadata is information about the image. We currently have a slide library of more than 10,000 images. Imagine all of those images in a folder on a hard drive with names like dsc1221.jpg. You would have to scroll for days to find the image you wanted. If you have a way of connecting metadata to an image; for example, an artist’s name, the title of the image, or the nationality of the artist, you make your search much easier.

As a studio artist interested in contemporary art, metadata isn’t usually complex. I just want my students to see some images and know who the artist is. But an art historian isn’t just teaching images, an art historian is also teaching research practices. And for someone interested in researching the history of images, all of that metadata is crucial. Additionally, as a studio faculty, I am usually willing to tolerate some sloppiness in my facts. But an art historian might be trying to teach students how to properly make a citation, in which case dates, titles, names, and facts need to be accurate.

A number of international organizations have collaborated to standardize metadata models. By collaborating on models, they make it easier to share databases of images. A common standard is called “Dublin Core”. You can find their web site at http://dublincore.org. The Dublin Core describes schemas for much more than images. The Visual Resources Association (the professional organization of slide librarians) has created a subset of the Dublin Core called the VRA Core. It is tailored to image data for adapting slide libraries to digital format. You can find information about it at their web site listed above.

So the first discussion, really, has been about organizing these images and what metadata needs to be recorded. Our art historian’s decision was to consider what metadata we already collect and use that as our starting point. The slides themselves are our current metadata model, each slide lists the artist, important dates, the title, etc. Our art historian felt like that would be sufficient. Exhaustive metadata really isn’t warranted in such a small collection, and a more intuitive solution of matching metadata with what is written on a slide is helpful. It also turns out that the simple information we already use is a subset of both the Dublin Core and VRA schema.

The database solution we have chosen to use is the Madison Digital Image Database, an open-source, web-based solution programmed in .NET run out of James Madison University (http://www.mdid.org). Our art historian has been talking with a number of art historians around the country, and everyone is telling him that MDID is becoming the standard. It is free, it is open-source, it uses a subset of the Dublin core, it can be configured to search other databases at affiliated institutions, and it has some built in tools that art historians want, like side-by-side display of images. The campus IT staff has actually had a copy of the MDID software for over a year. However, the software was written to run on a Windows server. IT was reluctant to use a Windows server on our network, because they are notorious for being insecure, and require a software license that we don’t own. More to the point, IT has been understaffed and simply hasn’t had the time to look at the project. Recently, the MDID team announced a Linux version. That made more sense, and since I am fairly comfortable with Linux (and Linux is free), I decided to go ahead and attempt an installation.

I used the windows box the college provides for my office (I use my own PowerBook for school). The software is now running on Ubuntu server edition (a kind of Linux), and right now the machine is located in the closet in the space that I use to store photography equipment, which has a live network port. The installation went fairly smoothly, but there are some issues.

It turns out that MDID on Linux is not great. Ideally, MDID would use a software package called Mono to emulate the .NET software that the Windows Server runs. Mono is supposed to work with an open source web server called Apache, but the connection between Apache and Mono is flaky. Apparently, less than half a dozen people in the country run MDID on Linux, and they are all having problems with Mono and Apache.

Mono has a built in web server that is less robust than Apache, and that is what I am currently running MDID on. The response to my questions about Linux on the MDID listserv was that in a school as small as ours, with a collection as small as ours, running MDID on the mono server (called XSP), was really not a problem. It’s only at schools where a database might see several hundred inquiries per second that it is really an issue. The art historian and I see this coming year (2006-2007) as an experiment to assess the server and how it can be integrated into the department. I believe that running the server like this will be fine for the meantime. But in the long run, we should be upgrading to a dedicated windows server, preferable something with a RAID array that will make backups painless. I would hope we could locate it in the computer center and not in my closet. I believe it will be fairly straightforward to migrate from server to server when the time comes.

The last point to make about MDID is that a proper installation would be useful to a lot of constituencies on campus. The biology department has a huge collection of field study slides, which could easily be hosted on the same MDID server in their own collection. Likewise, the Methodist archive, public relations, and the alumni office might all benefit.

Another important area we have researched is image capture. The art historian has really discerning tastes and feels it important to have the best possible images, especially when using them in the classroom.

We are using an Intel iMac as an imaging machine. I would prefer to have used an older machine, but the imaging software we are using (Apple’s Aperture) needs the most up-to-date processor we have. Additionally, we purchased a Canon Digital Rebel digital camera that with our existing copy stand for some of the image -capture work we are doing. Our art historian used art history course fees to purchase the copy of Aperture and a few large memory cards for the digital camera.

Aperture was chosen because it was one-third the cost of Photoshop for an academic copy, because Aperture deals very well with Camera RAW files, and because it is made to do the kind of correction and sorting of images that we will need in the slide library. Camera RAW files are very large files (6-8 megapixel) that are uncompressed and not color corrected. Basically, everything the camera sees is included in the Camera RAW file. Color correction for the file is done in Aperture after the image is imported. When Aperture deals with Camera RAW files, it never changes the original file until you explicitly export the image, so that the original large version can be archived and used at a later date.

In an ideal workflow, the copy stand and lights have been set at a known position, so that exposure settings never vary. A student worker would fill a memory card from books and other images, and unload the card into Aperture. In Aperture, I have saved an image with known black, white, and gray values taken on the copy stand under the same lighting conditions. A student worker would copy color balance and image correction settings from that calibration image and apply them to all of the incoming images. As long as the lights don’t move, we can expect accurate, consistent results with most exposures. And because Aperture doesn’t destroy the original image, we can change the exposure or cropping of an image at any later date. Full sized, Camera RAW files will be archived on an external drive.

At this point, the student worker would export the images as jpegs and upload them into MDID and enter relevant metadata. This is very time consuming because it requires accurately entering metadata into the system. I was only able to enter about 20 images per hour. However, if a faculty member were in a hurry for images, the student worker could email the jpegs, put them on a cd or usb memory stick, or put them on a network resource the faculty member can access.

When I showed our art historian the process of using the digital camera and Aperture, he became alarmed. The art historian and his student workers had already put more than five years of hard work into assembling the slide collection, and the thought of shooting all of those images again worried him. So we began looking at slide scanning resources. The flatbed scanner in our department can scan 35mm slides. It does a better job than most flatbed scanners. But the scans didn’t hold up when they were projected. The scanner does a better job with larger format film, and I am leaving it in the slide library because I want to use it with my photo students and am terrified that the dust in the rest of the department will destroy it.

The other solution we tried was having the slides scanned commercially, at a commercial lab here in Adrian. They have a much better scanner and they charge 90 cents per scan. These scans looked good, initially.

We thought that imaging the collection would call for a variety of approaches. For new images or images with terrible slides, using the copy stand and Canon DSLR is the quickest, cheapest, and best way to get images into the MDID system. However, our art historian wanted to put together several hundred or more important slides each semester and have the local lab scan them. He would pay for them out of art history course fees. We had discussed targeting one of the regular Western Art survey courses and getting the important images onto MDID first. The idea was that having one course ready to go on MDID would be a benefit to an incoming art historian and make the position look more attractive during our upcoming search. Finally, someone needing a quick-and-dirty scan of a slide is welcome to use the flatbed scanner in the slide library.

However, it soon became apparent that the quality of scans we could get from our local lab using slides from our collection was not good enough. The original slides we had in the collection were taken from books and magazines, the images we copied were often small, and the source books were old with poor color reproductions. As much as the art historian didn’t want to replicate the work that went into the original library, it was clear that we would have much better results just using a DSLR and the highest quality source material we could find.

Another significant issue is projecting images in the classroom. A number of classrooms in our building have digital projectors installed, including our Mac lab on the third floor. The art history room does not. We purchased a digital projector as part of a grant. The art historian in our department used art history course fees to purchase a wheeled cart and a Mac Mini (Apple’s low end, barebones computer).

Currently, we have the mini and projector on the cart. We can wheel the cart in from storage and project images. I have a wireless router on the first floor, directly above the classroom, and miraculously, we can pick up the signal through the floor, so we can access MDID or other web sites during class.

However, there are several issues with the projector. The projector really needs to be mounted on the ceiling. The lens is fairly wide angled, and to get an image you can see, the projector needs to be in a really awkward place in the classroom. Also, the art historian is willing to live with the poor color rendering of a projector, but finds the aspect ratio really distracting. It’s hard to project images side by side and have them large enough on the wall to be seen from the back of the room. He is investigating better projectors with wide aspect ratios and longer zoom lenses. But after looking on the art historian mailing lists, it becomes clear that there is no good solution to this problem, and programs everywhere are trying to cope with it.

It’s important to note that using digital images mean re-thinking pedagogical assumptions. The image quality and color balance of digital projectors is not yet as good as 35mm slides. However, digital images can be organized so that students can study them on the web. Digital images are useful review tools for exams so that students can work from their own dorm room. An on-line digital database means students can explore artists without needing access to the slide library. If we only think of digital images as replacing traditional projection of slides, they aren’t all that compelling. But if we embrace the new possibilities inherent in the medium, a whole range of teaching possibilities opens up.

I think it important to mention, in closing, that the current slide library is not going to change. Jeff, I, and the other faculty will still depend on it heavily, and we will keep the equipment for making 35mm slides in place. If any of our colleagues are uncomfortable with adopting digital images, there is no reason they have to do so until the last bulb in the last slide projector in the department has broken.

This summer the department’s art historian and I researched and began assembling a digital slide library. I wanted to apprise you of the scope of our research, the equipment we have put in place, and our plan to move forward for the next year.

Our art historian discussed this move with a number of art historians at other schools and we both searched through the archive of the Visual Resource Association web site (http://www.vraweb.org). One thing is clear; this is no simple undertaking. Most institutions have full time visual resource librarians with a staff helping them. They are often overwhelmed by the complexity of the job, and find the process time-consuming.

The other thing that became clear is that the real issue for slide librarians isn’t software or slide scanners (although they are important). The real issue is metadata. Metadata is information about the image. We currently have a slide library of more than 10,000 images. Imagine all of those images in a folder on a hard drive with names like dsc1221.jpg. You would have to scroll for days to find the image you wanted. If you have a way of connecting metadata to an image; for example, an artist’s name, the title of the image, or the nationality of the artist, you make your search much easier.

As a studio artist interested in contemporary art, metadata isn’t usually complex. I just want my students to see some images and know who the artist is. But an art historian isn’t just teaching images, an art historian is also teaching research practices. And for someone interested in researching the history of images, all of that metadata is crucial. Additionally, as a studio faculty, I am usually willing to tolerate some sloppiness in my facts. But an art historian might be trying to teach students how to properly make a citation, in which case dates, titles, names, and facts need to be accurate.

A number of international organizations have collaborated to standardize metadata models. By collaborating on models, they make it easier to share databases of images. A common standard is called “Dublin Core”. You can find their web site at http://dublincore.org. The Dublin Core describes schemas for much more than images. The Visual Resources Association (the professional organization of slide librarians) has created a subset of the Dublin Core called the VRA Core. It is tailored to image data for adapting slide libraries to digital format. You can find information about it at their web site listed above.

So the first discussion, really, has been about organizing these images and what metadata needs to be recorded. Our art historian’s decision was to consider what metadata we already collect and use that as our starting point. The slides themselves are our current metadata model, each slide lists the artist, important dates, the title, etc. Our art historian felt like that would be sufficient. Exhaustive metadata really isn’t warranted in such a small collection, and a more intuitive solution of matching metadata with what is written on a slide is helpful. It also turns out that the simple information we already use is a subset of both the Dublin Core and VRA schema.

The database solution we have chosen to use is the Madison Digital Image Database, an open-source, web-based solution programmed in .NET run out of James Madison University (http://www.mdid.org). Our art historian has been talking with a number of art historians around the country, and everyone is telling him that MDID is becoming the standard. It is free, it is open-source, it uses a subset of the Dublin core, it can be configured to search other databases at affiliated institutions, and it has some built in tools that art historians want, like side-by-side display of images. The campus IT staff has actually had a copy of the MDID software for over a year. However, the software was written to run on a Windows server. IT was reluctant to use a Windows server on our network, because they are notorious for being insecure, and require a software license that we don’t own. More to the point, IT has been understaffed and simply hasn’t had the time to look at the project. Recently, the MDID team announced a Linux version. That made more sense, and since I am fairly comfortable with Linux (and Linux is free), I decided to go ahead and attempt an installation.

I used the windows box the college provides for my office (I use my own PowerBook for school). The software is now running on Ubuntu server edition (a kind of Linux), and right now the machine is located in the closet in the space that I use to store photography equipment, which has a live network port. The installation went fairly smoothly, but there are some issues.

It turns out that MDID on Linux is not great. Ideally, MDID would use a software package called Mono to emulate the .NET software that the Windows Server runs. Mono is supposed to work with an open source web server called Apache, but the connection between Apache and Mono is flaky. Apparently, less than half a dozen people in the country run MDID on Linux, and they are all having problems with Mono and Apache.

Mono has a built in web server that is less robust than Apache, and that is what I am currently running MDID on. The response to my questions about Linux on the MDID listserv was that in a school as small as ours, with a collection as small as ours, running MDID on the mono server (called XSP), was really not a problem. It’s only at schools where a database might see several hundred inquiries per second that it is really an issue. The art historian and I see this coming year (2006-2007) as an experiment to assess the server and how it can be integrated into the department. I believe that running the server like this will be fine for the meantime. But in the long run, we should be upgrading to a dedicated windows server, preferable something with a RAID array that will make backups painless. I would hope we could locate it in the computer center and not in my closet. I believe it will be fairly straightforward to migrate from server to server when the time comes.

The last point to make about MDID is that a proper installation would be useful to a lot of constituencies on campus. The biology department has a huge collection of field study slides, which could easily be hosted on the same MDID server in their own collection. Likewise, the Methodist archive, public relations, and the alumni office might all benefit.

Another important area we have researched is image capture. The art historian has really discerning tastes and feels it important to have the best possible images, especially when using them in the classroom.

We are using an Intel iMac as an imaging machine. I would prefer to have used an older machine, but the imaging software we are using (Apple’s Aperture) needs the most up-to-date processor we have. Additionally, we purchased a Canon Digital Rebel digital camera that with our existing copy stand for some of the image -capture work we are doing. Our art historian used art history course fees to purchase the copy of Aperture and a few large memory cards for the digital camera.

Aperture was chosen because it was one-third the cost of Photoshop for an academic copy, because Aperture deals very well with Camera RAW files, and because it is made to do the kind of correction and sorting of images that we will need in the slide library. Camera RAW files are very large files (6-8 megapixel) that are uncompressed and not color corrected. Basically, everything the camera sees is included in the Camera RAW file. Color correction for the file is done in Aperture after the image is imported. When Aperture deals with Camera RAW files, it never changes the original file until you explicitly export the image, so that the original large version can be archived and used at a later date.

In an ideal workflow, the copy stand and lights have been set at a known position, so that exposure settings never vary. A student worker would fill a memory card from books and other images, and unload the card into Aperture. In Aperture, I have saved an image with known black, white, and gray values taken on the copy stand under the same lighting conditions. A student worker would copy color balance and image correction settings from that calibration image and apply them to all of the incoming images. As long as the lights don’t move, we can expect accurate, consistent results with most exposures. And because Aperture doesn’t destroy the original image, we can change the exposure or cropping of an image at any later date. Full sized, Camera RAW files will be archived on an external drive.

At this point, the student worker would export the images as jpegs and upload them into MDID and enter relevant metadata. This is very time consuming because it requires accurately entering metadata into the system. I was only able to enter about 20 images per hour. However, if a faculty member were in a hurry for images, the student worker could email the jpegs, put them on a cd or usb memory stick, or put them on a network resource the faculty member can access.

When I showed our art historian the process of using the digital camera and Aperture, he became alarmed. The art historian and his student workers had already put more than five years of hard work into assembling the slide collection, and the thought of shooting all of those images again worried him. So we began looking at slide scanning resources. The flatbed scanner in our department can scan 35mm slides. It does a better job than most flatbed scanners. But the scans didn’t hold up when they were projected. The scanner does a better job with larger format film, and I am leaving it in the slide library because I want to use it with my photo students and am terrified that the dust in the rest of the department will destroy it.

The other solution we tried was having the slides scanned commercially, at a commercial lab here in Adrian. They have a much better scanner and they charge 90 cents per scan. These scans looked good, initially.

We thought that imaging the collection would call for a variety of approaches. For new images or images with terrible slides, using the copy stand and Canon DSLR is the quickest, cheapest, and best way to get images into the MDID system. However, our art historian wanted to put together several hundred or more important slides each semester and have the local lab scan them. He would pay for them out of art history course fees. We had discussed targeting one of the regular Western Art survey courses and getting the important images onto MDID first. The idea was that having one course ready to go on MDID would be a benefit to an incoming art historian and make the position look more attractive during our upcoming search. Finally, someone needing a quick-and-dirty scan of a slide is welcome to use the flatbed scanner in the slide library.

However, it soon became apparent that the quality of scans we could get from our local lab using slides from our collection was not good enough. The original slides we had in the collection were taken from books and magazines, the images we copied were often small, and the source books were old with poor color reproductions. As much as the art historian didn’t want to replicate the work that went into the original library, it was clear that we would have much better results just using a DSLR and the highest quality source material we could find.

Another significant issue is projecting images in the classroom. A number of classrooms in our building have digital projectors installed, including our Mac lab on the third floor. The art history room does not. We purchased a digital projector as part of a grant. The art historian in our department used art history course fees to purchase a wheeled cart and a Mac Mini (Apple’s low end, barebones computer).

Currently, we have the mini and projector on the cart. We can wheel the cart in from storage and project images. I have a wireless router on the first floor, directly above the classroom, and miraculously, we can pick up the signal through the floor, so we can access MDID or other web sites during class.

However, there are several issues with the projector. The projector really needs to be mounted on the ceiling. The lens is fairly wide angled, and to get an image you can see, the projector needs to be in a really awkward place in the classroom. Also, the art historian is willing to live with the poor color rendering of a projector, but finds the aspect ratio really distracting. It’s hard to project images side by side and have them large enough on the wall to be seen from the back of the room. He is investigating better projectors with wide aspect ratios and longer zoom lenses. But after looking on the art historian mailing lists, it becomes clear that there is no good solution to this problem, and programs everywhere are trying to cope with it.

It’s important to note that using digital images mean re-thinking pedagogical assumptions. The image quality and color balance of digital projectors is not yet as good as 35mm slides. However, digital images can be organized so that students can study them on the web. Digital images are useful review tools for exams so that students can work from their own dorm room. An on-line digital database means students can explore artists without needing access to the slide library. If we only think of digital images as replacing traditional projection of slides, they aren’t all that compelling. But if we embrace the new possibilities inherent in the medium, a whole range of teaching possibilities opens up.

I think it important to mention, in closing, that the current slide library is not going to change. Jeff, I, and the other faculty will still depend on it heavily, and we will keep the equipment for making 35mm slides in place. If any of our colleagues are uncomfortable with adopting digital images, there is no reason they have to do so until the last bulb in the last slide projector in the department has broken.

Friday, January 19, 2007

Helmut Newton on Charlie Rose.

| Helmut Newton on Charlie Rose via video.google.com. I didn't realize Rose was so interested in photography. I also didn't figure Newton to be so down to earth. Casually tosses out "Annie" and "Dick" in reference to Leibovitz and Avedon - imagine living that career. The Newton interview starts at 28:00. | |

Photographer crush - Scott Dietrich

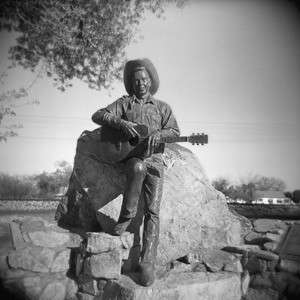

Image by Scott Dietrich.

I know Scott from the University of Arizona photography program. I caught up with him at the Society for Photographic Education conference last year in Chicago. He lives and works in Wisconsin/Chicago, and somehow managed access to architectural models by Frank Lloyd Wright in Taliesin. He’s been photographing them and the images are fantastic; mostly because they have been neglected for many, many years. They are covered in dust, torn and broken. So they are images not so much of Wright’s amazing architecture, but rather a post-apocalypse vision of Wright’s work. Awesome.

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Portraits and happy accidents.

I have been thinking about making portraits. Probably because I have been following Alec Soth's blog religiously lately. But mostly because I have never really dealt with the problem. Too scared to tell people what to do, too uncertain of what I want them to do.

Soth, August Sanders, Reneke Dijkstra, and Marcella Hackbardt (a friend from graduate school) all come to mind as photographers making portraits I admire - letting the portraits be straightforward, asking the subjects to address the camera. The images all play with that peculiarly photographic trait of believability, as if we are seeing an honest presentation of the self of the subject. I also enjoy the unadorned compositional choices. The subject isn't cropped, the setting is as telling as the person in the photograph and everything is placed right in the middle of the frame. Probably taken with a 4x5 and not a DSLR. Honest. Pragmatic.

So I was pleasantly surprised when I finished a 4x5 demo for my intermediate photography class and had a look at the Polaroids. This image floated out of the bunch, there were a couple of others too. Goo on the Polaroid back's rollers and poor focus aside, all the potential was present. It's as if the secret is setting up the camera and letting it sit in plain view for an hour, so that people forget it's in the room. Oh yeah, and having the power to grade them down if they don't participate.

For what its worth, a show put together by the George Eastman House came through the University of Michigan Museum of Fine Arts last year that was an overview of the history of photography. The representative image by August Sander was Bricklayer's Mate. I was shocked to get my nose up to the plexi and see how overtly the image had been manipulated and retouched. I seem to recall almost a quarter of the image being painted in black to get the luscious shadow in the negative space. I don't know why I would think that a turn-of-the-twentieth-century German photographer would be accountable to the expectations of F64, but it caught me off guard.

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

Geoffrey Batchen talk on photography and computer science.

This is a link to a video hosted at Brown University of a talk by photo-historian Geoffrey Batchen. In the talk Batchen traces the relationship between early photography and early computer science. He discusses the relationships between early innovators like Talbot and Charles Babbage. Really interesting stuff.

Monday, January 15, 2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)